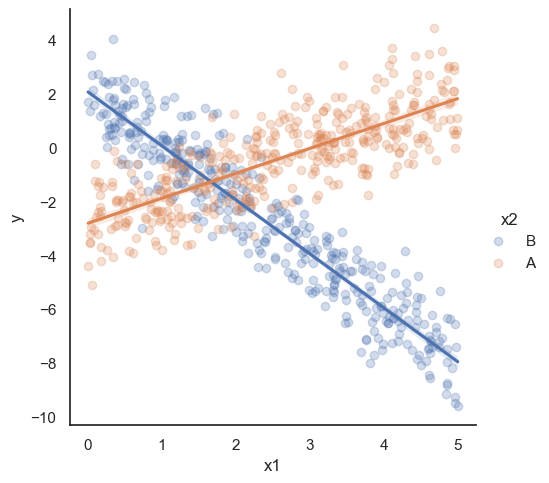

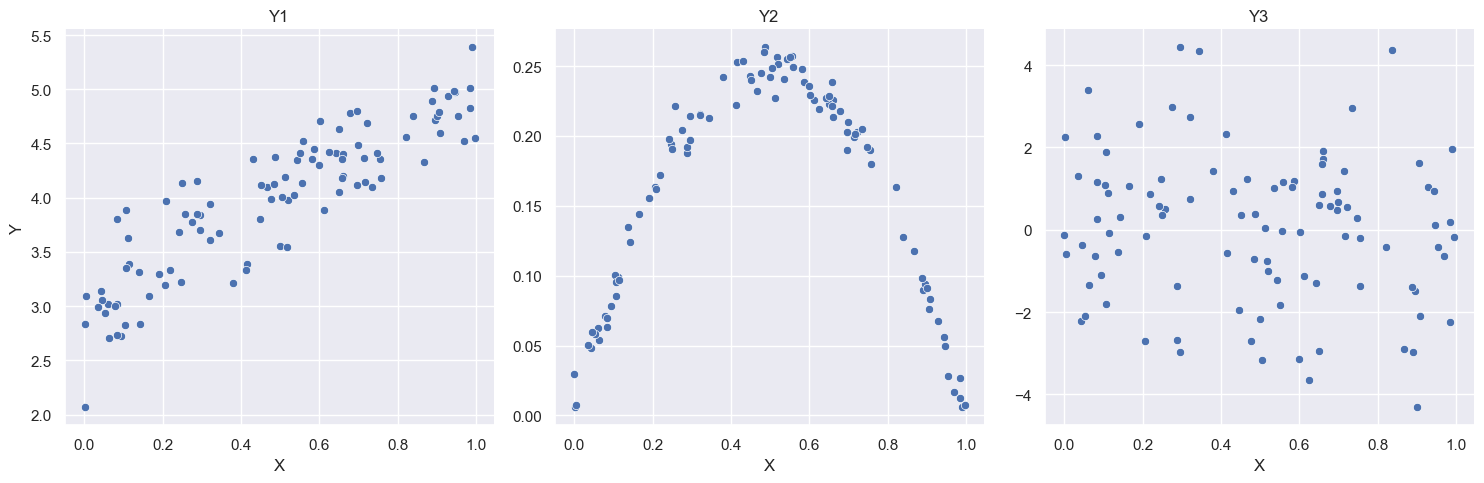

To carry on with our plan we introduce some notation. The equation of the regression line will be written as: \[

y = b_0 + b_1\, x

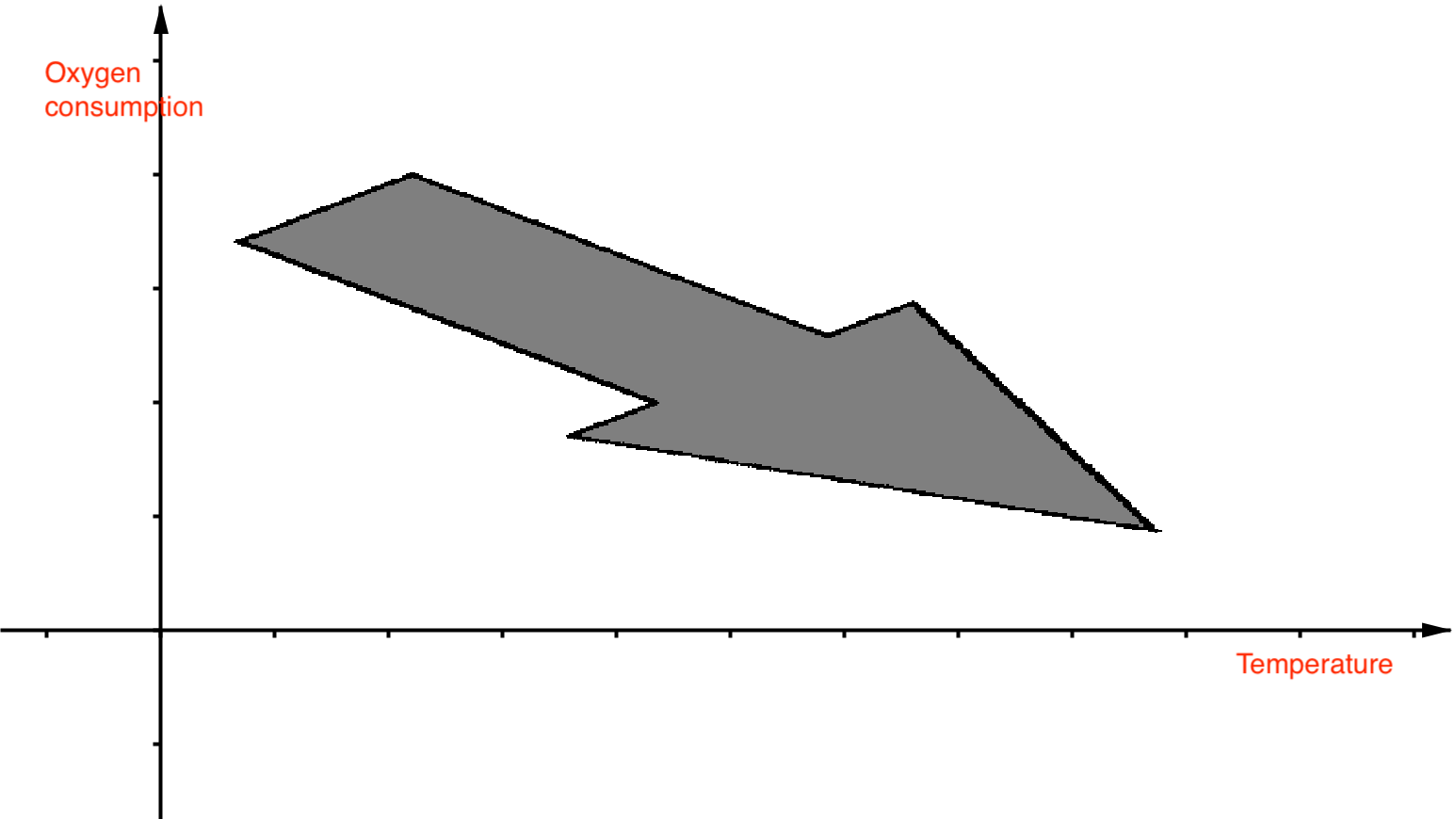

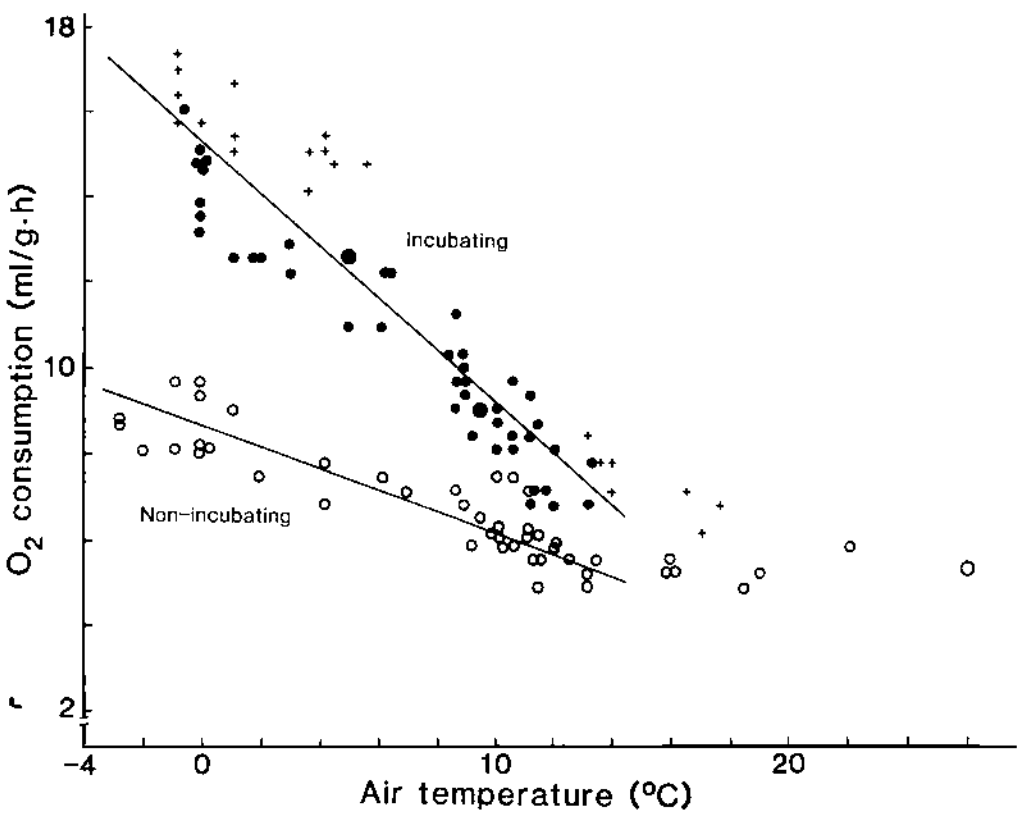

\] where \(b_1\) is the slope of the line. The sign of \(b_1\) reflects if the line is going up or down as we move to the right. Its absolute value equals how many units \(y\) changes when \(x\) changes by one unit. The value of \(y\) when \(x = 0\) is \(b_0\), the intercept.

Let us assume that \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) are known values. Then if the sample points are: \[

(x_1, y_1),\, (x_2, y_2), \ldots,\, (x_n, y_n)

\] when we plug each \(x_i\) in the equation of the regression line we get another value of \(y\) (usually different from \(y_i\)), that we call the predicted value and denote by \[

\hat y_i = b_0 + b_1\, x_i,\quad\text{for each }\quad i =1,\ldots,n

\]

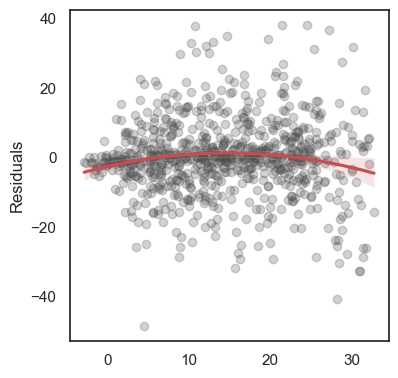

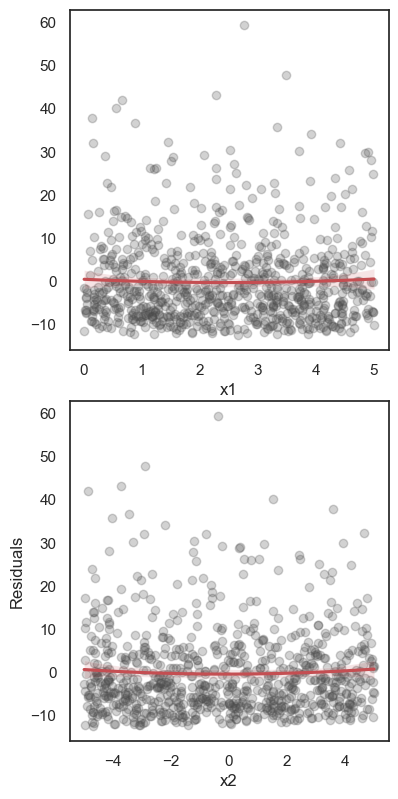

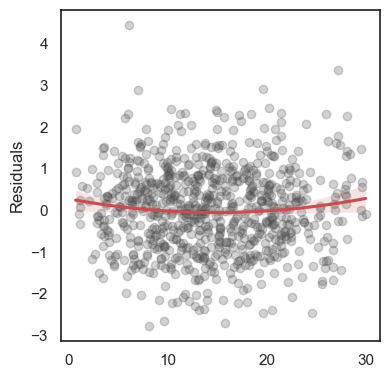

The residuals are the differences: \[e_1 = y_1 - \hat y_1,\,\quad e_2 = y_2 - \hat y_2,\quad \ldots\quad ,\,e_n = y_n - \hat y_n \]

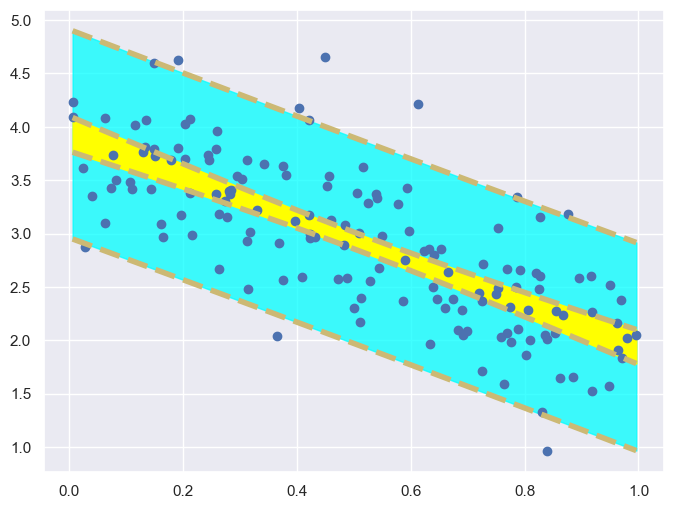

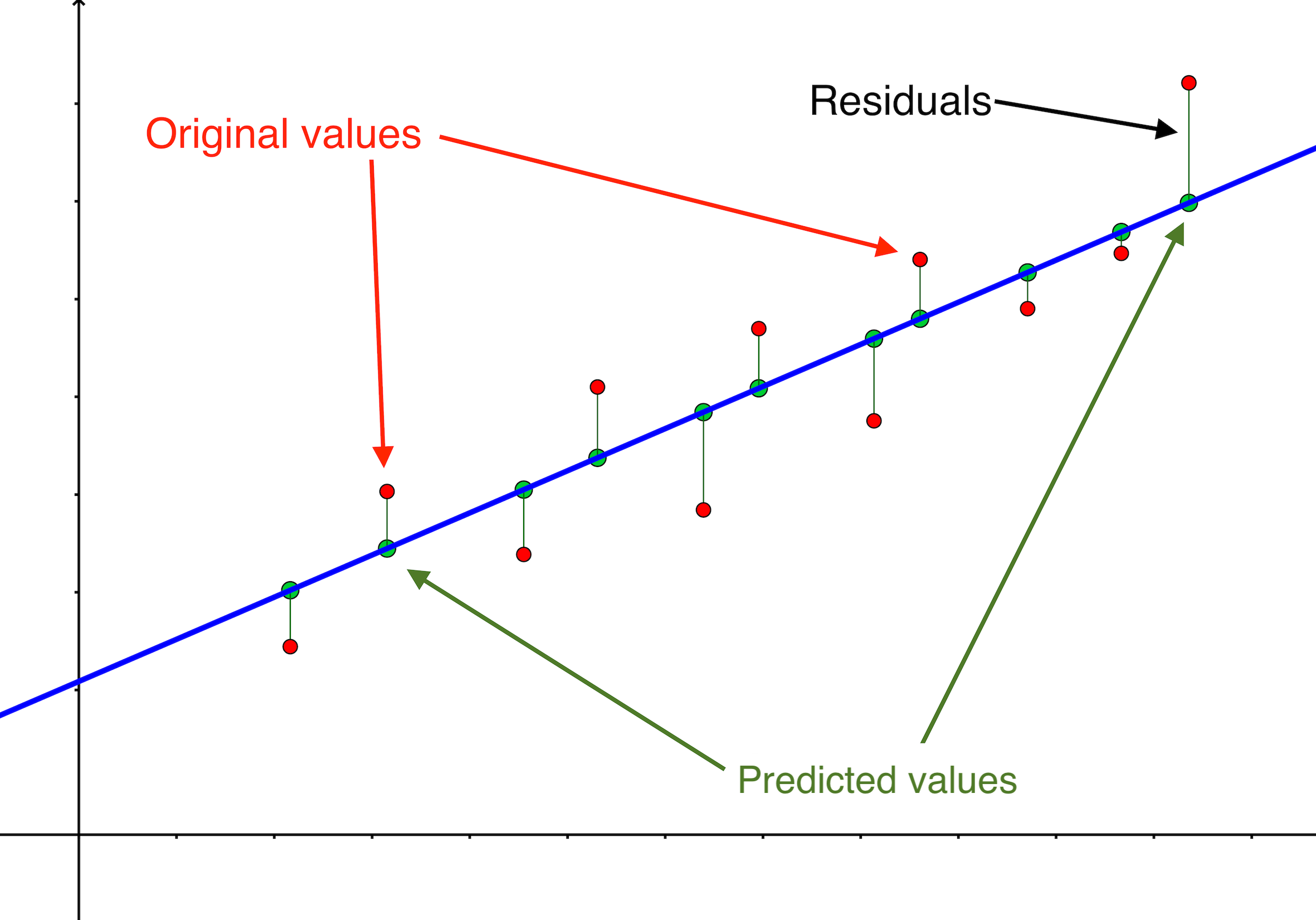

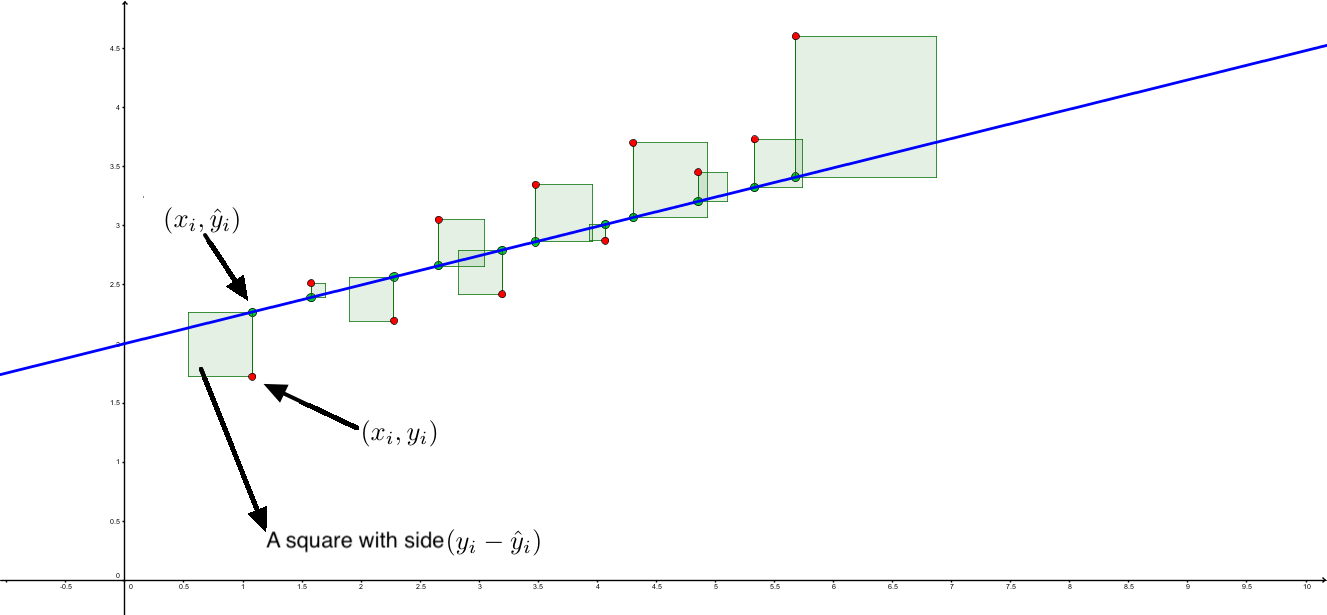

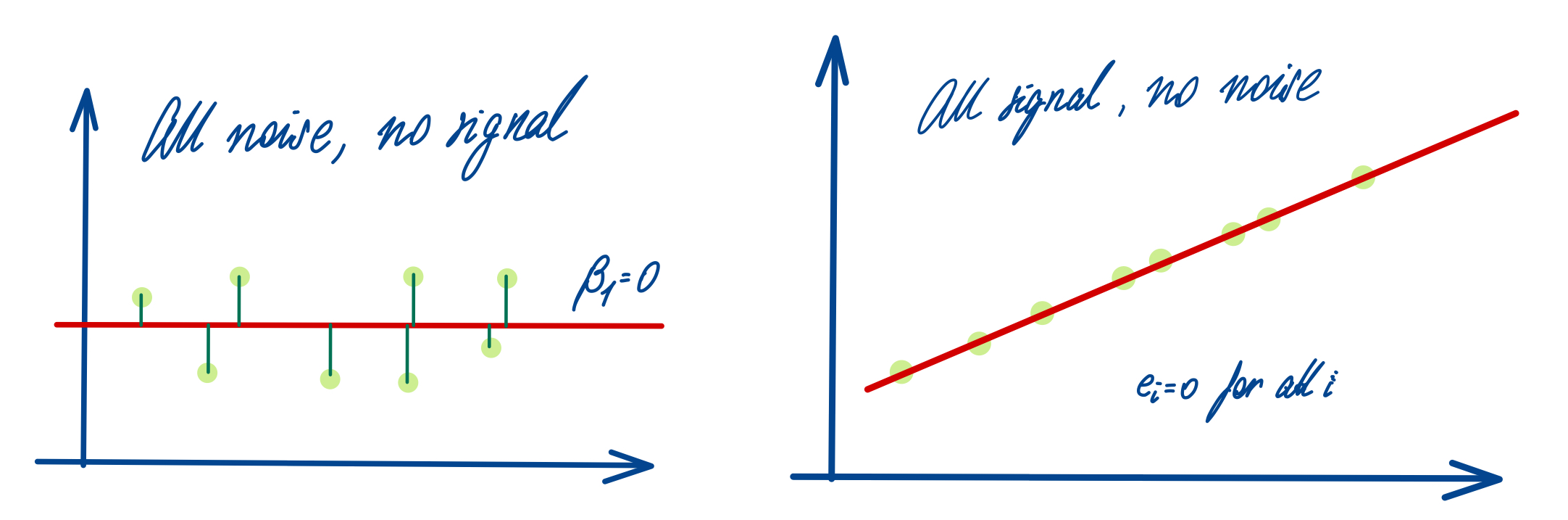

All these terms are illustrated in the figure below: + The red dots correspond to the original sample points, with (vertical coordinates) \(y_1, \ldots, y_n\). + The green dots are the predicted values, with \(\hat y_1, \ldots, \hat y_n\). + The residuals \(e_1, \ldots, e_n\) measure the lengths of the vertical segments connecting each red point to the corresponding green one.

{width75% fig-align=“center” fig-alt=“Interpretation of the Correlation COefficient”}

{width75% fig-align=“center” fig-alt=“Interpretation of the Correlation COefficient”}